Building a frequency hopping CTF challenge

For this year’s BSides Ottawa CTF, I built a number of software-defined radio challenges. (More about the CTF can be found in my previous post). One of my favourites was “Hopping along”, a four-part frequency hopping challenge.

When players tuned to 922.125 MHz, they were greeted with a narrow-band FM signal: “This is VE3IRR. The first flag is tango…” And then the signal hopped down to 922.025 MHz. Tuning there would reveal some more letters of the flag: “…victor echo uniform golf whiskey tango papa papa…” Next the signal hopped up to 922.450 MHz, providing the end of the flag: “…kilo sierra hotel delta victor tango charlie.” Of course, you’d invariably miss some of the letters while tuning from one frequency to the next. But since the signal repeated about once per minute, you could camp out on any one of the three frequencies and wait for the piece you were missing to be transmitted again. Players were awarded with 50 points for putting together the three pieces.

Then the problem got harder. Part two (worth 100 points) was similar, except that the signal hopped once per second. This challenge could be completed in a similar fashion, as long as you had a lot of patience. Part three (worth 150 points) had 5 hops per second, and part four (worth 200 points) had 50 hops per second! Clearly these were too hard to be solved by hand, and so a better approach was needed.

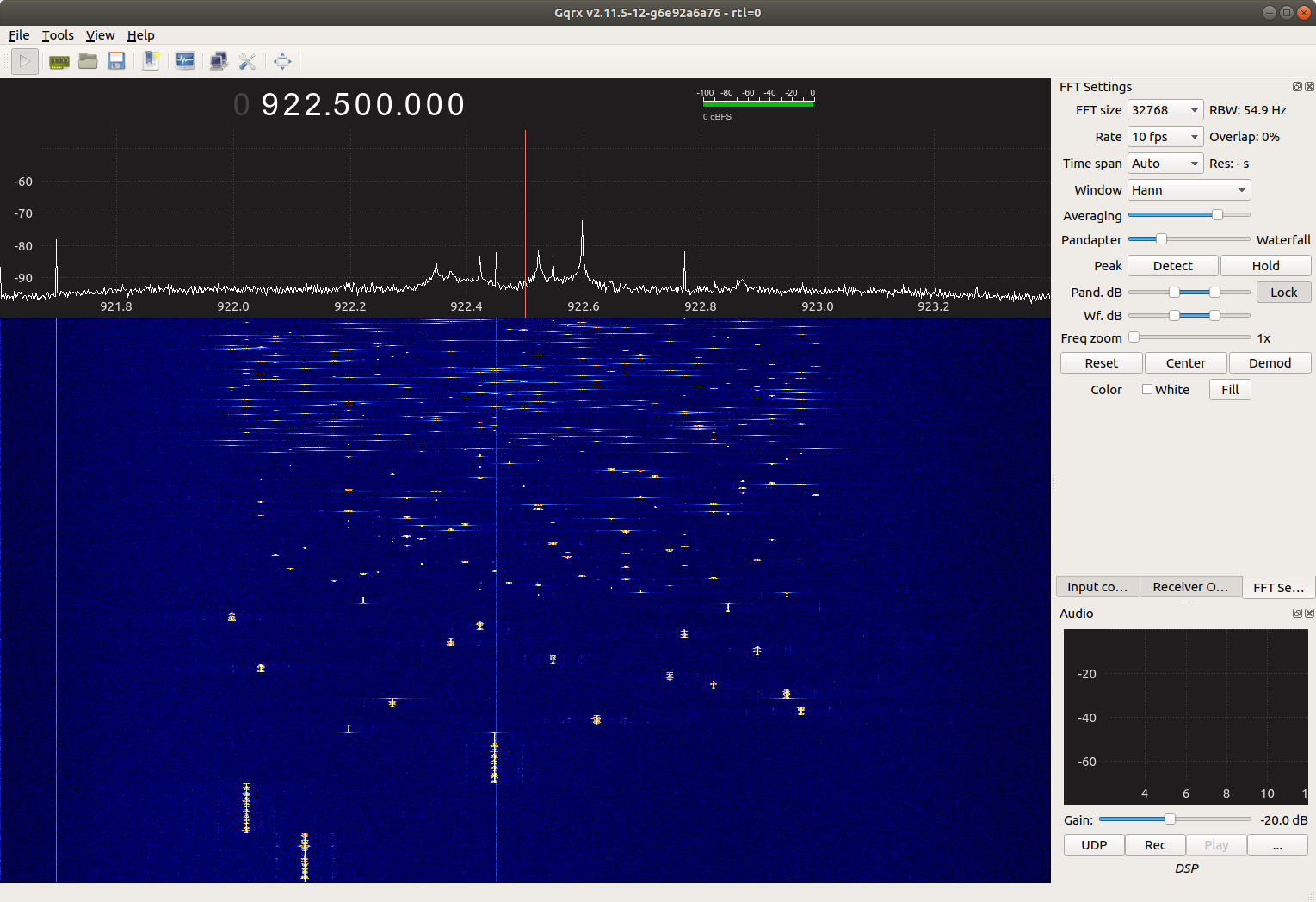

Here’s how things looked on the waterfall, with part one at the bottom and part four at the top:

There are several ways to approach this problem, but the end goal is always the same: to remove the hopping component from the signal so the audio can be demodulated.

My favourite approach is to take advantage of aliasing. Usually aliasing is a bad thing, because it causes two or more input frequencies to map to the same output frequency, making them indistinguishable. But in the case of a frequency hopping signal, it would actually be helpful if all the channel frequencies were mapped into a single one! To make this happen, all we need to do is sample the signal at some integer multiple of the channel spacing, then downsample the signal by keeping one out of every n samples, where n is the ratio of the sample rate to the channel spacing.

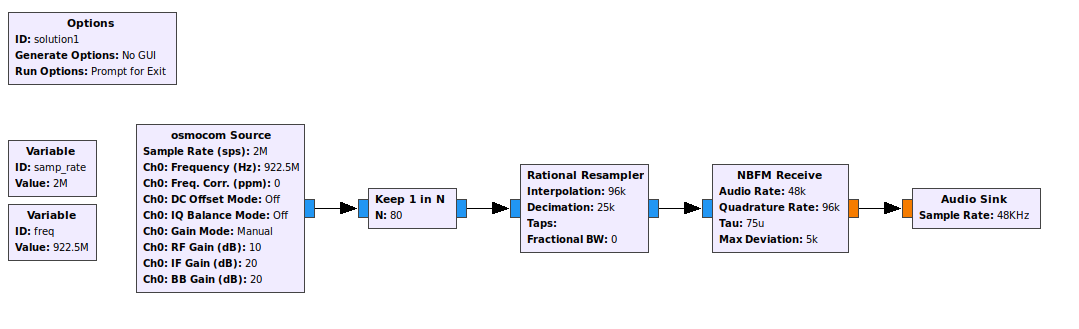

In this case, the channel spacing is 25 kHz, so we can sample the signal at 2 MHz and keep one out of every 2,000,000 / 25,000 = 80 samples. GNU Radio provides a “Keep 1 in N” block to do exactly that. We can then increase the sample rate back to a more convenient 96,000 samples per second and run it through an FM demodulator:

One disadvantage of this approach is that the noise in all the channels is combined. But as long as the signal-to-noise ratio is high and only a single channel is transmitting at a time, that’s not a problem. This receiver works beautifully, and all the flags can easily be heard.

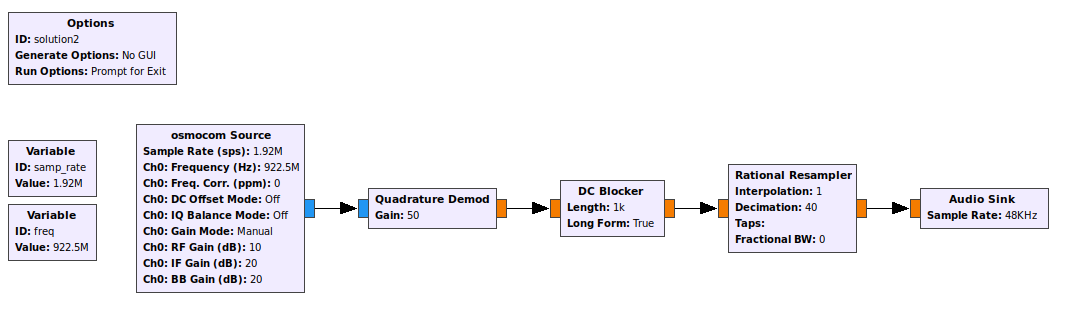

Another approach is to demodulate the entire band as if it was a single FM signal. This will result in a step function being added into the audio signal. Since this step function is mostly a DC signal, we can remove it with a DC Blocker (a special type of high-pass filter):

This mostly works, but a noisy “pop” bleeds through the filter every time a hop occurs. In part four this results in a loud buzz at 50 Hz, but the flag can still be heard.

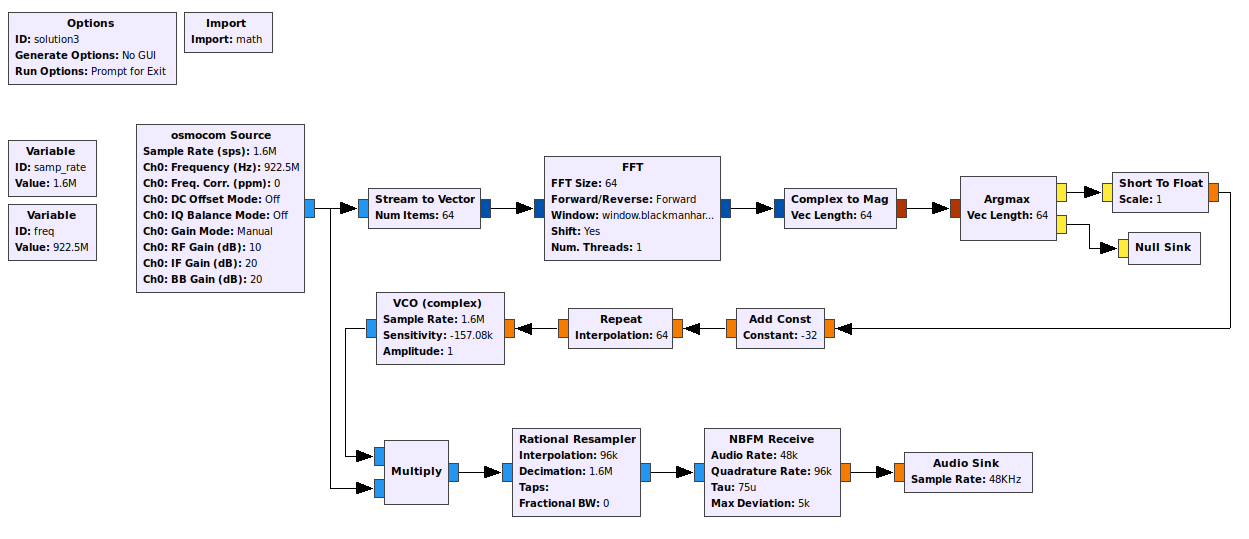

A third approach, which a friend of mine came up with during the competition, is to use a fast Fourier transform to detect which channel is active, and use that information to shift the input signal up or down in frequency so as to map the active channel’s frequency to zero. Here I’ve used an Argmax block to detect which FFT bin contains the most energy, a VCO (voltage controlled oscillator) block to generate a signal whose frequency is the negative of the active channel’s offset, and a Multiply block to combine the VCO with the input signal, shifting the frequency up or down as required:

This flow graph provides a very clean output signal, and would work well even if the signal-to-noise ratio was lower.

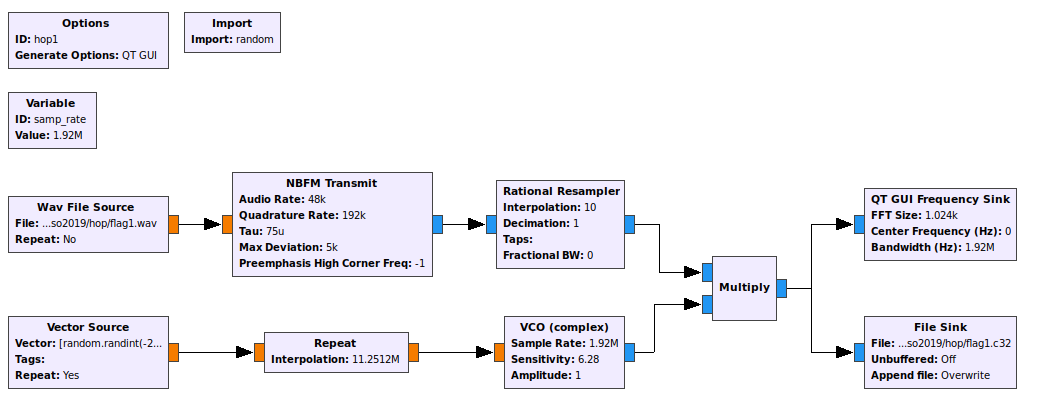

In case you’re curious, here’s the GNU Radio flowgraph I used to create sample files for each of the four parts of the challenge. The Vector Source and Repeat blocks generate a random step function, and the VCO and Multiply blocks shift the FM signal up or down in frequency in proportion to the step function.

In the end, 16 teams solved part one, four got part two, and two teams got all four parts.